Bodhidharma

Baizhang Huaihai

Caoshan Benji

Dahui Zonggao

Daman Hongren

Danxia Tianran

Dayi Daoxin

Dazhao Puji

Dazhu Huihai

Dazu Huike

Deshan Xuanjian

Dongshan Liangjie

Dōgen

Eisai

Guifeng Zongmi

Guishan Lingyou

Guizong Zhichang

Heze Shenhui

Hongzhi Zhengjue

Huangbo Xiyun

Huanglong Huinan

Huineng

Jinshan tanying

Linji Yixuan

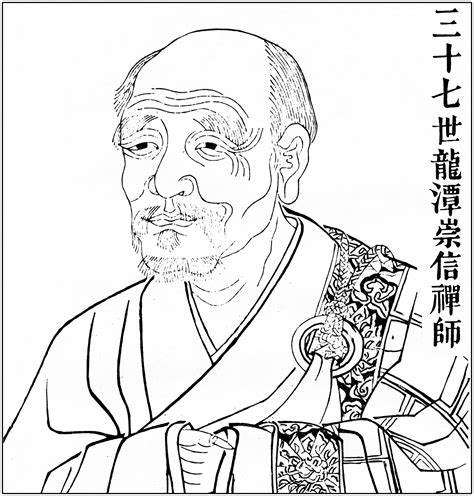

Longtan Chongxin

Luohan Guichen

Mazu Daoyi

Nanquan Puyuan

Nanta Guangyong

Nanyang Huizhong

Nanyue Huairang

Niutou Farong

Qingliang Wenyi

Qingyuan Xingsi

Sengcan

Shishuang Chuyuan

Shitou Xiqian

Tianhuang Daowu

Xiangyan Zhixian

Xitang Zhizang

Xuansha Shibei

Xuedou Chongxian

Xuefeng Yicun

Yangqi Fanghui

Yangshan Huiji

Yantou Quanhuo

Yaoshan Weiyan

Yongjia Xuanjue

Yongming Yanshou

Yunmen Wenyan

Yunyan Tansheng

Yuquan Shenxiu

Zhaozhou Congshen

Index

Longtan Chongxin

born

782

died

865

religion

Chan

teacher

Tianhuang Daowu

students

Deshan xuanjian

Contents

Introduction

with Master Deshan Xuanjian

Introduction

Lung-t'an came from a poor family, who made their living by selling pastry. Tao-wu master knew him as a boy, and recognized in him great spiritual potentialities. He housed his family in a hut belonging to his monastery. To show his gratitude, Lung-t'an made a daily offering of ten cakes to the master. The master accepted the cakes, but every day he consumed only nine and returned the remaining one to Lung-t'an, saying, “This is my gift to you in order to prosper your descendants.” One day, Lung-t'an became curious, saying to himself, “It is I who bring him the cakes; how is it then that he returns one of them as a present to me? Can there be some secret meaning in this?” So the young boy made bold to put the question before the master. The master said, “What wrong is there to restore to you what originally belonged to you?” Lung-t'an apprehended the hidden meaning, and decided to be a novice, attending upon the master with great diligence. After some time, Lung-t'an said to the master, “Since I came, I have not received any essential instructions on the mind from you, master.” The master replied, “Ever since you came, I have not ceased for a moment to give you essential instructions about the mind.” More mystified than ever, the disciple asked, “On what points have you instructed me?” The master replied, “Whenever you bring me the tea, I take it from your hands. Whenever you serve the meal, I accept it and eat it. Whenever you salute me, I lower my head in response. On what points have I failed to show you the essence of the mind?” Lung-t'an lowered his head and remained silent for a long time. The master said, “For true perception, you must see right on the spot. As soon as you begin to ponder and reflect, you miss it.” At these words, Lung-t'an's mind was opened and he understood. Then he asked how to preserve this insight. The master said, “Give rein to your Nature in its transcendental roamings. Act according to the exigencies of circumstances in perfect freedom and without any attachment. Just follow the dictates of your ordinary mind and heart. Aside from that, there is no ‘holy' insight.”

Lung-t'an later settled in Lung-t'an or the Dragon Pond in Hunan. A monk once asked, “Who will get the pearl amidst the curls of hair?” (Like the “priceless pearl” of the Bible, this expression apparently is a symbol for the highest wisdom hidden in the midst of the phenomenal world). Lung-t'an answered, “He who does not fondle it will get it!” “Where can we keep it?” asked the monk further. Lung-t'an replied, “If there is such a place, please tell me.”

A nun asked Lung-t'an as to what she should do in order to become a monk in the next life. The master asked, “How long have you been a nun?” The nun said, “My question is whether there will be any day when I shall be a monk.” “What are you now?” asked the master. To this the nun answered, “In the present life I am a nun. How can anyone fail to know this?” “Who knows you?” Lung-t'an fired back.

The famous Confucian scholar, Li Ao, once asked Lungt'an, “What is the Eternal Wisdom?” The master replied, “I have no Eternal Wisdom.” Li Ao remarked, “How lucky I am to meet Your Reverence!” “Even this it is best to leave unsaid!” the master commented.

with Master Deshan Xuanjian

Lung-t'an was instrumental in the conversion of Te-shan Hsüan-chien (780-865). Te-shan, born of a Chou family in Cheng-tu, Szechuan, began early as a member of the Vinaya order, steeped in scriptural learning. He made a special study of the Diamond Sutra on the basis of the learned commentaries of the Dharma master Ch'ing-lung. He lectured on this sutra so frequently that his contemporaries nicknamed him “Diamond Chou.” Later, hearing about the prosperity of the Zen platform in the south, he became indignant and said, “How many homeleavers have spent a thousand kalpas in studying the Buddhist rituals, and ten thousand kalpas in observing all the minute rules of the Buddha. Even then they have not been able to attain Buddhahood. Now, those little devils of the south are bragging of pointing directly at the mind of man, of seeing one's self-nature and attaining Buddhahood immediately! I am going to raid their dens and caves and exterminate the whole race, in order to requite the Buddha's kindness.”

Carrying on a pole two baskets of Ch'ing-lung's commentaries, he left Szechuen for Hunan, where Lung-t'an was teaching. On his way, he encountered an old woman selling pastries, which in Chinese were, and still are, called “mind-refreshers.” Being tired and hungry, he laid down his load and wanted to buy some cakes. The old woman, pointing at the baskets, asked, “What is this literature?” He answered, “Ch'ing-lung's commentaries on the Diamond Sutra.” The old woman said, “I have a question to ask you. If you can answer it, I will make a free gift of the mind-refreshers to you. But if you cannot, please pass on to another place. Now, the Diamond Sutra says: ‘The past mind is nowhere to be found, the present mind is nowhere to be found, and the future mind is nowhere to be found.' Which mind, I wonder, does Your Reverence wish to refresh?” “Te-shan had no word to say, and went on to Lung-t'an. After he had arrived at the Dharma hall, he remarked, “I have long desired to visit the Dragon Pond. Now that I am here on the very spot, I see neither pond nor dragon.” At that time, the master Lungt'an came out and said to him, “Yes, indeed, you have personally arrived at the true Dragon Pond.” Te-shan again had nothing to say. He decided to stay on for the time being. One evening, as he was attending on the master, the latter said, “The night is far advanced. Why don't you retire to your own quarters?” After wishing the master good night, he went out, but returned at once, saying, “It's pitch dark outside!” Lung-t'an lit a paper-candle and handed it over to him. But just as he was on the point of receiving the candle, Lung-t'an suddenly blew out the light. At this point, Te-shan was completely enlightened, and did obeisance to the master. The master asked, “What have you seen?” Te-shan said, “From now on, I have no more doubt about the tongues of the old monks of the whole world.”

Next morning, the master ascended to his seat and declared to the assembly, “Among you there is a fellow, whose teeth are like the sword-leaf tree, whose mouth is like a blood-basin. Even a sudden stroke of the staff on his head will not make him turn back. Some day he will build up my doctrine on the top of a solitary peak.”

On the same day, Te-shan brought all the volumes of Ch'ing-lung's Commentaries to the front of the hall, and, raising a torch, said, “An exhaustive discussion of the abstruse is like a hair thrown into the infinite void, and the fullest exertion of all capabilities is like a little drop of water falling into an unfathomable gulf.” Thereupon he set the commentaries to fire.

This episode is not merely spectacular but profoundly suggestive. It recalls to mind what Lao Tzu has said, “Where darkness is at its darkest, there is the gateway to all spiritual insights.” In the present instance, the night was dark enough, but it became infinitely darker after the candle was lit and blown out again. When all external lights were out, the inner light shone in all its effulgence. But, of course, this did not work automatically. It worked in the case of Te-shan because his mind was just at that moment ready for the enlightenment. The little chick was stirring in the egg and trying to break through the shell; and it took just a peck by the hen on the outside to effectuate the breakthrough.

Te-shan's act of burning the learned commentaries and his realization that all discursive reasonings of the philosophers were no more than a hair in the infinite void should remind us of that St. Thomas Aquinas in his last days said to his secretary who was still urging him to continue his writing: “Reginald, I can do no more; such things have been revealed to me what all the writings I have produced seem to me like a straw.”

Contact us

Disclaimer

Comments

© Copyright Jumpypixels.com