Bodhidharma

Baizhang Huaihai

Caoshan Benji

Dahui Zonggao

Daman Hongren

Danxia Tianran

Dayi Daoxin

Dazhao Puji

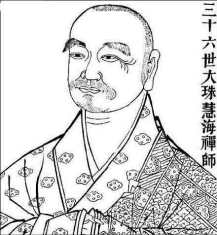

Dazhu Huihai

Dazu Huike

Deshan Xuanjian

Dongshan Liangjie

Dōgen

Eisai

Guifeng Zongmi

Guishan Lingyou

Guizong Zhichang

Heze Shenhui

Hongzhi Zhengjue

Huangbo Xiyun

Huanglong Huinan

Huineng

Jinshan tanying

Linji Yixuan

Longtan Chongxin

Luohan Guichen

Mazu Daoyi

Nanquan Puyuan

Nanta Guangyong

Nanyang Huizhong

Nanyue Huairang

Niutou Farong

Qingliang Wenyi

Qingyuan Xingsi

Sengcan

Shishuang Chuyuan

Shitou Xiqian

Tianhuang Daowu

Xiangyan Zhixian

Xitang Zhizang

Xuansha Shibei

Xuedou Chongxian

Xuefeng Yicun

Yangqi Fanghui

Yangshan Huiji

Yantou Quanhuo

Yaoshan Weiyan

Yongjia Xuanjue

Yongming Yanshou

Yunmen Wenyan

Yunyan Tansheng

Yuquan Shenxiu

Zhaozhou Congshen

Index

Dazhu Huihai

born

?

died

?

religion

Chan

POSTH name

Chan Master Qingyan

teacher

Mazu Daoyi

works

The Path to Sudden Attainment

Contents

biography

biography

ZEN MASTER DAJU HUIHAI, whose name means “Great Pearl Wisdom Sea,” lived and taught in the late eighth and early ninth century. Daju was a senior and foremost disciple of Mazu Daoyi. He came from Yue Province, a place in Southeast China, and became a monk with a preceptor named Zhi at Great Cloud Temple, also in Yue Province. Daju Huihai is said to have had a bulbous forehead, which led to his Dharma name “Great Pearl.”

His biography relates that upon first meeting Mazu, the following exchange took place:

Mazu asked, “From where have you come?”

Great Pearl said, “From Yue Province.”

Mazu then asked, “What were you planning to do by coming here?”

Great Pearl said, “I've come to seek the Buddhadharma.”

Mazu then replied, “I don't have anything here, so what ‘Buddhadharma' do you think you're going to find here? You haven't seen the treasure in your own house, so why have you run off to some other place?”

Great Pearl then said, “What is the treasury of the wisdom sea?”

Mazu then said, “It is just who is asking me this question, that is your treasury. It is replete, not lacking in the slightest, and if you realize its embodiment then why would you go seeking it elsewhere?”

Upon hearing these words, Daju perceived his fundamental mind unobstructed by thinking. He ardently thanked and honored Mazu [for this instruction].

The paradox at the heart of Zen, and the antimetaphysical way that Zen approached this paradox, are at the center of the following exchange between a Tripitaka master—a teacher of the Buddhist Vinaya (Precepts) school—and Zen master Great Pearl:

A Buddhist Tripitaka master asked Great Pearl, “Is the Tathagata [‘True Thusness'] subject to transformation or not?”

Great Pearl answered, “It transforms.”

The Tripitaka master said, “The Zen master is mistaken.”

Great Pearl then asked the Tripitaka master, “Is there such a thing as the Tathagata?”

The man replied, “Yes, there is.”

Great Pearl then said, “Then if [you think] it doesn't change, then you're just an ordinary [unenlightened] monk. Haven't you heard that worthies who perceive [the truth] can transform the three poisons into the pure precepts; that they can transform the six senses into the six miraculous powers; that they turn defilements into wisdom, and that they turn what is doubtful into great wisdom? If [you think] the Tathagata does not transform, then you are truly a ‘naturalism' heretic.”

The Tripitaka master then said, “If that's so, then the Tathagata does undergo transformation.”

Great Pearl then said, “If you cling to the idea that the Tathagata undergoes transformation, then that is also an incorrect view.”

The Tripitaka master then said, “You just said that the Tathagata undergoes transformation, but now you say it doesn't change. How can you properly speak in this manner?”

Great Pearl said, “If you completely understand the nature [of mind], it's like the appearance of the mani jewel [that fulfills wishes]. You can say it changes, and you can say it doesn't change. Among those who have not observed the nature [of mind], when they hear that the Tathagata undergoes change, they have some [false] understanding that it undergoes transformation, and if someone says to them that the Tathagata is not subject to change, then they have some [false] understanding about it not undergoing transformation.”

The Tripitaka master then said, “This is why the Southern school [of Zen] is considered to be unfathomable.”

Zen master Great Pearl authored a text entitled Doctrine of the Vital Gate of Sudden Entry into the Way that lays out an unusually detailed and concise explanation of how the “Southern” Zen school viewed itself and its practice of “sudden” enlightenment. Written in the form of questions and answers between a student and an unidentified Zen master, the text establishes meditation as the basic method for understanding the nature of the mind, and uses this context to clarify points of doctrinal confusion.

Here follows some short excerpts from the text:

Student: What is the method through which one may gain liberation?

Teacher: There is only the “sudden” method by which one may gain liberation.

Student: What is the “sudden” method?

Teacher: “Sudden” is to suddenly forgo all delusive thoughts. “Enlightenment” is [to know that] no enlightenment can be attained.

Student: How does one practice this?

Teacher: It is practiced from what is fundamental [literally, from the “root”].

Student: How does one practice from the fundamental?

Teacher: Mind is fundamental. Student: How does one know that mind is fundamental? Teacher: The Lankavatara Sutra says, “When mind manifests, all the myriad dharmas are manifested. When mind is extinguished the myriad dharmas are extinguished…”

Student: When a person practices the fundamental, what method do they use?

Teacher: Only Zen meditation [is this practice]. It is achieved through Zen samadhi.

Student: “Form is emptiness” and “the mundane is sacred”. Are these things [realized through] sudden enlightenment?

Teacher: Yes.

Student: What is [the meaning of] “form is emptiness.” What is [the meaning of] “the mundane is sacred”?

Teacher: When the mind contains defilements, that is “form.” When the mind is undefiled that is “emptiness.” When the mind is polluted it is ordinary mind. When the mind is unpolluted then it is “sacred.” It is also said that because there is true emptiness therefore there is form. But because there is form, it does not follow that there is emptiness. What is now called emptiness, [means] the self-nature of form is empty. If there is no form, then emptiness [is also] extinguished. What we now call “form” is empty of self-nature. Form does not come from [the same] form [i.e. is not eternal].

The “paradox” in Zen is enhanced by a linguistic problem in passages such as the above. Part of the ambiguity and confusion surrounding ideas of “emptiness” arise from the fact that there is no clear distinction in Chinese between the adjective empty and the noun emptiness . The word kong has both or either implication. When the word is interpreted as “empty,” then the teaching on the emptiness of things may be interpreted to mean “things are empty of self nature.” This view conforms with the classical Zen Buddhist perspective that there is no underlying metaphysic in the nature of things. However, when the same word is interpreted as “emptiness,” a noun, then the interpretation “form is emptiness” leads those who hear or read the phrase to believe a metaphysical emptiness underlies form, and form itself is erroneously thought to have an idealist underpinning. Great Pearl avoids this pitfall by describing form and emptiness simply as qualities of thought. In this way, he avoids the pitfall of metaphysical interpretation and remains true to basic Zen teachings of the Bodhidharma line.

Zen master Great Pearl speaks to the signless practice, the practice of the “third hall,” in the following exchange from the Compendium of Five Lamps.

Vinaya master Yuan asked Great Pearl, “When you practice the Way, do you use a special skill?”

Great Pearl said, “I do.”

Yuan asked, “What is it?”

Great Pearl said, “ When I'm hungry I eat. When I get sleepy I sleep.”

Yuan said, “Everyone does these things. Do they not have the same skill as you?”

Great Pearl said, “They do not have the same skill.”

Yuan said, “Why is it not the same?”

Great Pearl then said, “When

hey eat it can't be called eating, since they do so [while involved] with a hundred entanglements. When they sleep it can't be called sleeping, since their mind is beset with worries. Thus they are not the same.” The Vinaya master was silent.

The place of Zen master Great Pearl's death is unknown.

Contact us

Disclaimer

Comments

© Copyright Jumpypixels.com